The Illegal Age by Ellen Hinsey

The word ‘important’ is over-used in poetry reviews, but in the case of Ellen Hinsey’s The Illegal Age it seems to me the only appropriate adjective to describe a sequence which should be required reading on the National Curriculum. It is not a book we can afford to ignore; and I’m very grateful to the Poetry Book Society as I had heard of neither the book nor the poet before it came through the post as their Autumn Choice.

Like Robert O. Paxton’s 2005 The Anatomy of Fascism, this is a book which approaches its subject with the absolute clarity it requires. Paxton set out his analysis of Fascism as an ‘Anatomy’ almost as though it were a body lying out for dissection, Hinsey uses the structure of legal documentation as the framework which both supports and contains her poetic project. In the same way that the restrictions of a strictly-rhymed sonnet simultaneously create and contain its content, The Illegal Age’s three sections or ‘investigation files’ (Smoke, Ice and Obscurity – themselves divided legalistically into Reports, Evidence, Files, Internal Reports, more Evidence, more Files, and Testimony) allow Hinsey both to build a Kafkaesque edifice (though perhaps ‘scaffold’ would be a more appropriate, sinister word) that confines her language – and by restraining creates its meanings – and becomes a mysteriously self-contained world in which her own investigation can take place: What are these documents? Who is on trial? Who is sitting in judgement? Well, it would seem that autocracy itself is in the dock, indeed being condemned and imprisoned by its own dark strictures, but if that is the case there is no sense that we as readers are in any position of power – perhaps we may think ourselves members of some small resistance group rifling through the documentation of the collection by torchlight.

Paxton pointed out that Fascism is never inevitable because throughout its stages of development there are always (among other factors) people making choices, but Hinsey uses her unfolding imagery, her changes of register, her rhythms and motifs (in other words her poetic ‘choices’) to begin a process of unpacking at a deeper level than is possible in non-fiction prose (or arguably fictional prose) and we as readers are aware that the analysis taking place here is occurring at some point behind or beyond the mere political fact of totalitarianism itself. The barriers of those clouding, opaque section titles hint at the impossibility of the feat the book is attempting (or asking us to attempt) which is an analysis of what Hinsey calls ‘the autocratic experience’, but which could equally be called the soul of totalitarianism.

“Nothing happens quickly:” is the declarative that opens the book, the first of many (most sections take the form of lists of either aphorisms, instructions or Old Testament-style injunctions), and one which sets the tone – it is another expression perhaps of Hannah Arendt’s image in The Origin of Totalitarianism in which the “subterranean streams” of Jewish history lead to the great “coming to the surface” of the Holocaust; “each day weighs upon the next” Hinsey continues, “until the instant comes”. And that is in essence what this sequence goes on to scrutinise – the semi-hidden approach and then the ‘surfacing’ of a moment of total tyranny.

The distillation of this moment comes through most succinctly I think in ‘Elementary Lesson in Division’, a prose poem (or ‘anti-lyric’ to use Hinsey’s chosen phrase) which takes the logic of algebraic equations as a starting point from which to reduce and collapse an individual’s life, and by extension society, as the extreme clarity of mathematical language becomes analogous with the inhumanity of Nazi or Stalinist policy. The beginning and end of the poem run as follows:

“Start, as once instructed, on the left side of

the equation: there you will glimpse the totality

of a simple, well-ordered room……all is reduced to one, where

only a fraction of the face is left visible, then only

only a mouth, only a black eye through the bars –

before the prison train jolts.”

And so simple order is ultimately broken down to a single black zero, the hole of a political eternity. Here, with “as once instructed”, it seems to me that Hinsey deliberately echoes Geoffrey Hill’s “As estimated, you died” in his ‘September Song’; and this exemplifies how she writes “in dialogue with” other writers, as Marilyn Hacker puts it in the dust cover blurb. And this is one of the ways in which the book maintains a sense of hope amid the fear and despair. Just as we might think of ourselves as coming across these legal papers during some imagined act of defiance against the regime, there is also a feeling that poets of the past (Trakl, Celan, Szymborzka, and Milosz all more obvious examples than Hill) are being marshalled into a form of resistance which, while it survives, is our defence against the “ascendency” of “the Inconceivable” (‘On the Rise of the Inconceivable’). And part of this resistance is also the plea that the reader listens to other voices from the past, survivors of the Holocaust and other atrocities of autocracy: “Remember: each memory salvaged from tyranny’s flood is an unsteady, but miracle-buoyed raft” (‘Carved Into Bark’).

Although there remains a silence at the very centre of this work (“FINIS MUNDI You can then do what will never be able to be described in language” – ‘Handbook of Smoke’), many sections juxtapose registers that resist one another to create a friction from which the reader senses a voice expressing the individual experience within totalitarianism. The poem which seems to illustrate this best is ‘Terminology Lesson’, which uses eleven phrases that sound as though they may have been taken directly from a Secret Service handbook on torture (‘stress positions’, ‘special positions’, ‘sleep management’ etc.) as subtitles for brief statements and semi-statements which may or may not be biblical paraphrases but which certainly use the high religious-lyricism of the King James Bible (“Like each creature, beneath my tongue I possess a Word, given at birth – a Word that means to be and to praise –”; “And when before thee Lord, we were afraid, and before your justice –”). The horrific banality (recalling Arendt’s use of the word) of the torture-expressions imprisons the poetic beauty of the ‘personal-belief’ phrases leaving us stunned, perhaps numbed, by what the poem implies but cannot quite say.

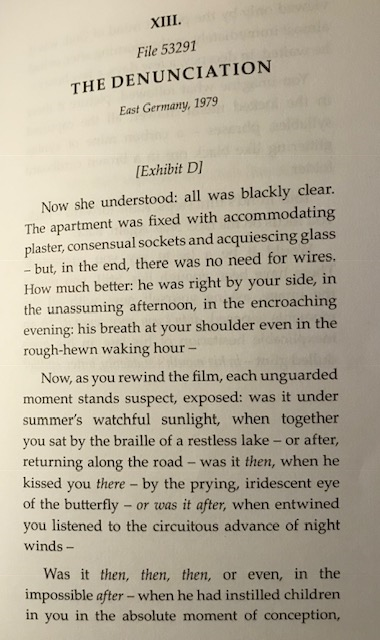

Torture techniques can be described in all their horrific detail, as can the factual details of what makes a fascist regime, for example, recognisable as such, but what Hinsey achieves in this sequence is a terrifying sense of being within the system, and further than that she stimulates readers to consider the implications of that terror for ourselves at our current, dangerous point in Western history. In ‘The Denunciation’ she elicits a horrific feeling of the personal paranoia and the invasion of private spaces by wider political spaces, not by telling us about it but by burrowing into a couple’s most intimate, spiritual, sexual moment – the moment of their child’s conception, and surrounding it with the language of espionage: video tapes, locked metal drawers and cardboard folders. At what point did the betrayal take place, the speaker asks. The total state has infiltrated and infected the deepest most private connections within the most personal relationships and has thereby achieved its aim. It is hard not to read this and think about the way the internet brings our public and private lives together and how that could and can be used to divide us from one another.

It is worth concluding this review, I think, by inserting the whole of ‘The Denunciation, as its effect is cumulative, and by noting that the phrase in its first line “all was blackly clear” may well be an echo of another voice, this time Holocaust survivor Paul Celan’s, from his famous ‘Death Fugue’: “Black milk of daybreak we drink it at sundown” (Michael Hamburger trans.).

There are many voices in this sequence, both above and below the surface, but all of them ask us to listen, and to remember.

The Illegal Age is published by Arc and is available here.