I’ve liked The Poetry Exchange’s regular podcast project Poems as Friends since I heard John Prebble and Andrea Witzke Slot’s conversation with Nicholas Laughlin the editor of The Caribbean Review of Books about the Martin Carter poem ‘Proem’. Laughlin’s disarming reading of this difficult-to-pin-down poem as he and his hosts notice things about it which have not struck him previously, his openness in accepting a level of non-understanding (“not an irresolute but not a resolved poem”) along with his insights into individual lines and a positioning of the poem in its political context struck me as a very healthy approach to poetry, and one which comes through in all these Poems as Friends episodes (there are more than fifty of them now). The idea of embracing a poem as a friend you wish to spend time with as oppose to a trophy you wish to hold aloft on social media as evidence of your great reading fits perfectly with the ideas around Responsibilities of the Reader that I posted about recently. It is also an approach which seems very anti-Cancel Culture to me, and while I think Cancel Culture is in some ways a misnomer for the phenomenon of principled people finding a voice for protest (let’s face it, there are aspects of Culture that can do with being Cancelled), it also has a knee-jerk, baby-out-with-the-bathwater side to it which Poems as Friends resists. The most recent episode, featuring actor, writer and director Stephen Beresford talking to Fiona Bennett and Michael Shaeffer about Larkin’s ‘Vers de Société’, is a very good example of this warts-and-all friendship aspect of The Poetry Exchange’s philosophy.

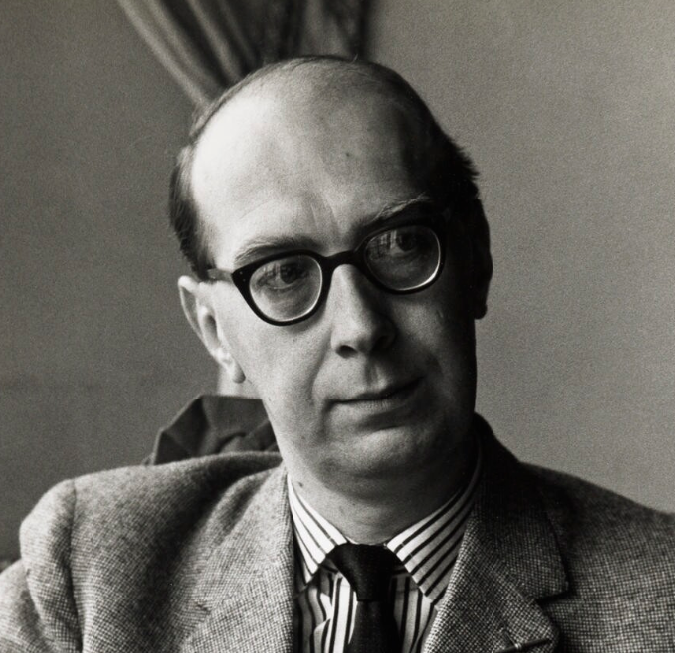

Philip Larkin, of course, if he has not already been cancelled is, along with Ted Hughes, ripe for the cancelling. He ticks all the boxes for the problematic dead white male poet category, and it would be silly to deny that there are elements of his writing which are not only out of kilter with contemporary sensibilities but objectively snobbish, racist and sexist. It’s the misogyny, not to mention the intellectual snobbery, as Bennett and Beresford point out, which comes through in ‘Vers de Société’ in the line “…to catch the drivel of some bitch / Who’s read nothing but Which”. But Beresford says at the beginning of this conversation that for him “(this poem) is the friend that most other people don’t like, and they say the wrong thing, and there’s a WhatsApp group where people discuss how terrible they are…and because of their unpopularity, because they’re difficult, I find as I’ve got older I’ve more and more grown to respect them”. This is the real strength of Poems as Friends. Some people will read an article like the one linked above and decide that Larkin lies on the wrong side of the good/bad divide, taking their relationship with him no further than that; but others will recognise the idea of an imperfect friend – one who you know well enough to be able to appreciate their good qualities, which stand side-by-side with their bad ones to make them a fully-rounded person. And it is hard not to acknowledge that sometimes the most difficult individuals can (in spite of and because of that) also be amongst the most talented, creative and profound.

The problematic line in this poem stands side-by-side with “Funny how hard it is to be alone”, “…looking out to see the moon thinned / To an air-sharpened blade”, “Too subtle that. Too decent, too. Oh hell.” and “Beyond the light stand failure and remorse” in a tightly-structured rhythmical pattern and fluctuating rhyme scheme. And there is something in knowing that a poet has written bad lines (and bad poems) which makes them seem rather more human and even increases your respect for there good lines and poems.

It is in fact the play of the beautifully expressed melancholy in Larkin against his intense miserablism that makes him the unique poet he is. Measure, for example, the complexity of hope expressed in ‘The Trees’ which caused me to pick that poem to read at my son’s funeral, against the attention-grabbing naughtiness, the ‘sayability’ yet the simple truth, that runs through ‘This be the Verse’ (the first lines of which my own mum happily quoted at me a few years ago).

It’s the latter of these two Larkin voices which brings us the gift of “In a pig’s arse, friend.” in ‘Vers de Société’, and to which Beresford rightly pays tribute. I don’t know whether this would be best formally rendered prosodically as an anapaest followed by a spondee or a pyrrhic followed by a molossus, but either way it is immensely satisfying to say, carrying exactly the right weight of intonation, vulgar imagery and conceptual juxtaposition to raise it from the level of ‘insult’ to ‘poetic insult’, which is itself an under-valued genre of poetry. This is the kind of line, the kind of poetry, which would not be possible without the arrogance and sense of entitled snobbery which also manifests in more seriously ugly ways on occasion. There is no reason for us to ignore or forgive Larkin for his faults in order to celebrate him for his more profound and enjoyable moments. I’m very grateful to The Poetry Exchange for reminding us that poetry, like friendship, doesn’t always have exist on a good-bad spectrum.

The conversation here is amusing and intelligent, and the readings are very well done (as always in these podcasts); Beresford’s comments on writing and loneliness are particularly apposite: “There are two massive things that if you want to be a human being and alive in the world you have to negotiate, and they are being alone and being with other people”.

If you haven’t come across The Poetry Exchange yet, I would recommend taking a look and having a listen.