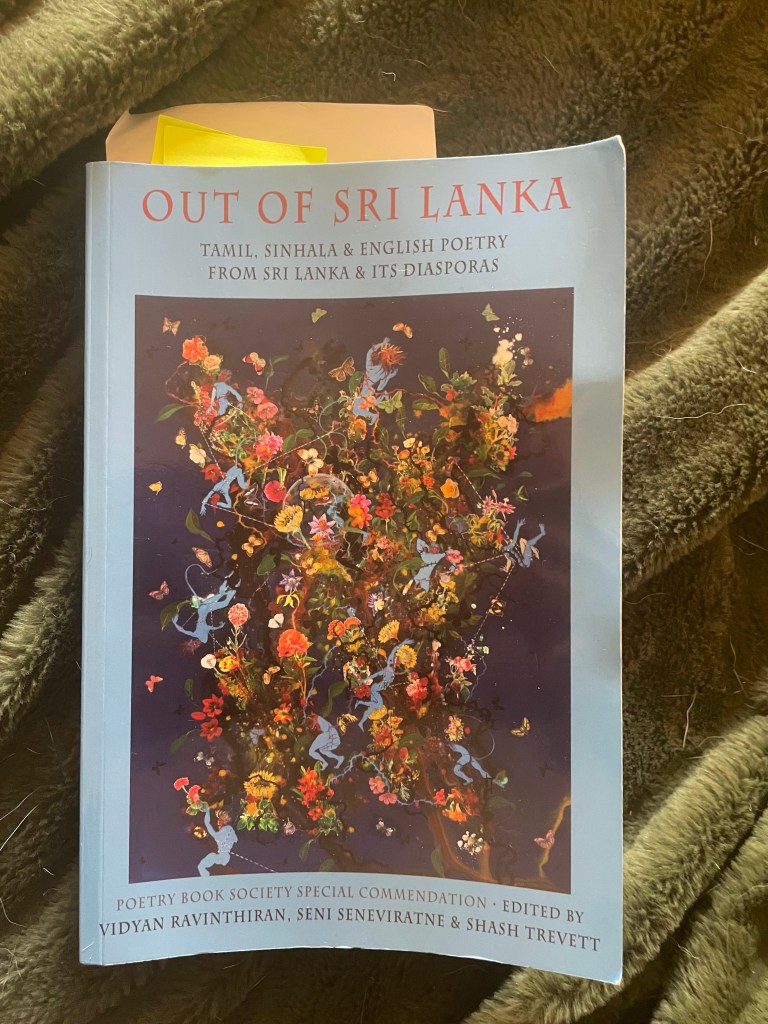

Out of Sri Linka: Tamil, Sinhala & English poetry from Sri Lanka & its diasporas

Eds. Vidyan Ravinthiran, Seni Seneviratne & Shash Trevett

There is an interesting phrase in Gordon Weiss’s 2011 book on the root causes and final days of Sri Lanka’s 26-year civil war, ‘The Cage’. Weiss describes the careful record keeping and desperate telephone calls of a small group of Tamil government doctors who were trapped along with thousands of civilians in the ‘siege zone’ as the Sri Lankan army finally closed in on the Tamil Tigers. These were, Weiss says, integral to “the compilation of memory” that subsequently provided evidence of atrocity that would otherwise have been obliterated entirely. “Instinctively (the doctors) understood better than most that the only gravestone that those who died would receive would be in the form of the ticks and marks on a hospital casualty form”, he writes, and “…(o)ften the UN would speak to the doctors from their radiotelephones, listening to their pleas for help and intervention while the dull sound of exploding shells crackled up the line…” (p276).

There is a comparison to be made I think (albeit one that I have to be careful in making) between the heroically steady and precise record keeping of those doctors, and their real-time testimonies of witness, and the enormous job of compilation that the three editors of this first ever anthology of Sri Lankan and diasporic poetry have undertaken. The voices that they allow to emerge, rising as they do from both within layers of division inside Sri Lanka over the last 60 or 70 years, and from around the world as the diasporic community has grown over the same period, create a rich and varied psychological/political landscape which is as unique – and often as harrowing – as the experience of Sri Lankans over the period since independence from British colonial rule in 1948. It is hard not to read this project of anthologisation as one in which a compilation is taking place so that a shared cultural memory is not obliterated by the deliberate forgetfulness of the powerful global forces that shape history.

Something in the region of 140 poets are represented in the anthology and as such it is quite an imposing tome, especially if, as it was for me, all but a handful of them are entirely unfamiliar names. But for that same reason, sitting down to read it – and to use it as a springboard to learn more about the country and its shocking recent past – was an exciting as well as an imposing prospect.

The editors have presented the poets in alphabetical order, almost always my preference in anthologies but in the case of this volume literally the only realistic choice, as attempting to divide them into the three linguistic/cultural/political strands represented here would have been disastrous and entirely against the spirit of the book. Those strands of course are central to the anthology as they are to the country but binding them together through the randomness of the first letter of the poets’ surnames locks them into a unity that transcends their wild differences. It also allows for ‘serendipitous connections’ as the editors say in their introduction; and making these connections was part of the joy of reading this anthology. The introduction provides names to get you started (George Keyt as springboard for English language Sri Lankan poetry; Mahakavi – pen name of Thuraisamy Rudhramurthy – for Tamil; and Siri Gunasinghe for Sinhala) and then the potted biographies that precede each poet’s work allow you to follow familial and sometimes literary connections that make you feel as though you are on a guided journey of discovery. But above this are the more genuinely chance juxtapositions that you come across if you follow the anthology in order (which I did for the As and Bs until I increasingly allowed myself to be led by the editors and pot luck); Tamil shoulder to shoulder with Sinhalese, shoulder to shoulder with Burgher – but of course these encounters also go further than ethnic/linguistic communities, they put the Hindu beside the Buddhist, the old beside the young, the radical beside the more traditional, the immediately horrific and terrifying beside the reflective and the humorous. Also, the dead beside the living, although taking 1948, the year of independence, as its general (sometimes ignored) starting point, there are more living than dead poets here.

An example of the editors’ successful approach to presenting the poems comes right at the beginning where the first and third poets in the anthology, Aazhiyaal and Packiyanathan Ahilan (Tamils) stand either side of the second, Bashana Abeywardane (Sinhalese). ‘Manampri’ by Aazhiyaal references the shocking rape and murder – described in the poem’s footnote – of a young left-wing student and a Tamil woman to evoke the menace of male violence still stalking the streets like a hungry animal (“The avid hunger in those eyes / makes me aware of an unknown tongue”). Ahilan’s ‘Corpse No. 182’ gives a brief, harrowing description of the discovered corpses of a mother and child in the terrifyingly cold language of the administrator (“They were fused into one body. // I cleaned them and noted them down: / Corpse No. 182.”). And sandwiched between these two, what should we make of the cautious note of optimism Abeywardane sounds in ‘The Window of the Present’ which unites he “long dead” of both the north and the south: “Nightmares, long dead, / peer through the shattered panes of the / window of the present” before hinting that the memory of them may give reason of hope: “But who is to say / that even this July a breath of summer’s hope, would not / steal through the shattered panes of the window of the present.” Abeywardane’s tentative sense of the hope represented by remembering the violence of the past, already weak (indeed its very weakness within the poem is ironically what carries its power) feels altogether suffocated by the horrors presented in the work of the two poets either side of him. If this reads as a criticism of bringing these three poets together, it is not meant as one; an anthology of poetry representing such a divided country over such an unspeakably blook-soaked seventy or so years, needs to deal with the sheer scale of the unimaginable violence of four more or less contiguous civil wars. Any sense of hope needs surely be weighed against the terrible psychological burden of recent history that must (and I can only guess here of course) be carried by many if not all Sri Lankans. The chance juxtaposition of these three poets seems to give a sense of this burden, which is why I think it is a good example of what the editors’ choice to present the poets alphabetically has added to this anthology.

I mentioned the introduction in passing earlier, and it is worth emphasising what an important essay this is, setting the general context of Sri Lanka politically since 1948 (though of course not going into detail, the editors recommend three books which will allow the reader to gain a more complete understanding of the country, ‘The Cage’ is one, and they are all linked below) and crucially providing a few pages of context for Tamil, Sinhala and Anglophone poetry as well as a note on civil war poetics, and also on what they term the eccentric poetries included in the volume. This eccentricity is in part referring to the fact that some poems here are not written by poets at all but by “photographers, government workers, novelists (and) journalists…who were pressed by extraordinary circumstances towards a lyric recognition of complexities otherwise beyond understanding”. But it also refers to “a strong, unexpected current of dark humour” which the editors point out both opposes and survives the “malaise akin to psychic numbing” which can result, according to late academic Malathi de Alwis, from “several decades of living with unrelenting violence and atrocity”. They are right about both its unexpectedness and its strength.

The following, from V.V. Ganeshananthan, a diaspora writer based in Minnesota, turns the atrocities of 2009 and other violence into a series of tongue-twisters, corrupting the childlike innocence of ‘She sells seashells’, evoking the relentless bombing of civilians on the beach, while letting neither the Tamil Tigers nor the government forces off the hook, particularly skewering then-Prime Minister Mahinda Rajapaksa. It is quite astonishingly effective and memorable, and it is undeniably shot through with bitter humour:

The misters assisted in shelling these shells on the seashore war, The shells they shelled were not sea-shells, I’m sure. ... And as the misters shelled the seashore during the war The terrorists held the people as shell-shields before - Hard to say. Hard to ring any bells. What are tongue-twisters for? 2 The mighty military mounted a magnificent Mullivaikkal monument to most magnanimous majesty Mahinda. Mahinda manages most magnificently militarily! (from ‘The Five-year Tongue Twisters’)

Not all the poems are concerned directly with post-independence violence, and another level of humour comes through in other more traditionally influenced poets, such as Regi Siriwardena, who (in ‘Birthday Apology and Apologia’) makes it through four stanzas of twenty lines each to mark his eightieth birthday before finishing with the relief of a slightly grumpy old man “And so, to quote a poet I never liked, / ‘Port after stormy seas.’ To all those friends / Too many to be named – who’ve helped me past / The whirlpool and the rocks, my heartfelt thanks. / This makes eighty pentameters. THE END.” I can imagine the poet putting his pen down with a clunk, sitting back in his chair and reaching for a large drink at this point.

Many poems here are written by those of the diaspora who look back on Sri Lanka (in space and/or time) from different kinds of exile and reflect on the country they or their family has been forced to leave. These poems often have a special strength that comes, I think, from a simultaneous distance and proximity they have in relation to the horrors suffered in their homeland. Thiru Thirukkumaran for example is a Tamil poet who lives in Ireland:

Even now, as the winter snow lies scattered across the doorway, spilled like the brains from a friend’s shattered skull, I cannot be rid of my memories. (‘Resurrection’)

And Dipti Saravanamuttu is a poet and academic who moved to Australia with her family in 1972:

In ‘88, the Sri Lankan civil war is your permanent backdrop to reading eighteenth-century novels and theorising the (gendered) subject. ‘Sinhalese subversives... Tamil terrorists’ someone reads to the meeting, from a conservative newspaper. listening to this stuff feels like an exercise in learning how the enemy thinks – ‘Rhetorical indoctrination’ you say grimly, and everyone laughs. (‘Landscape Art’)

For both these poets, the dissonance between their out of Sri Lanka experience with memories and events rooted within the country itself creates a gap which cannot quite be given expression but which their poetry seeks to fill. For many of the diasporic poets represented here, the gap is also generational, and their poetry often appears to be filling it by reflecting on notions of home and belonging. The following is by one of the anthology editors, Vidyan Ravinthiran, who is caught in a world where ‘home’ means very different things to him and his parents – and we are left to wonder what a family home means at all if it means something different to parents and their children, and indeed what then does being away from home mean?:

...by ‘home’, I mean the house my parents live in and where I grew up; like and unlike them saying ‘back at home’ when they intend Sri Lanka, and not Leeds where they live and I haven’t, not for years. (‘Ceylon’)

Part of the magic of any anthology is that it allows the reader to see links, themes, ironies, patterns that they would have been very unlikely ever to have found without the diligent work of the editor(s), and this one is no different. I was satisfyingly struck by a reference to cobwebs in a phrase quoted in the biogaphy of Kala Keerthi Carl Muller (a satirist, whose poem ‘Deiyyo Saakki!’ would certainly fit into the aforementioned category of the ‘darkly humorous’) which sent my mind straight back a much earlier poem in the anthology, by Parvathi Solomons Arasanayagam.

The Muller quote:

I feel there is no necessity to elevate Nature and tell of those same old time-worn things like “Gossamer cobwebs” and “silver moon-shafts” and “golden daffodils”.

Arasanayagam, from ‘Human Driftwood’:

Sometimes the walls I gaze on are blank but silence has its own language, I watch intently the perfection of spider webs forming on those whitewashed spaces, delicate yet tensile, feel my own mind in the filaments of that complex weaving.

It is as though the younger Arasanayagam has heard the point Muller makes, and she has said, yes what you say is true, but there are different ways of elevating nature. And she frees the cobwebs of their (possibly colonial) time-worn romantic meanings to use them as one of life’s “endless metaphors” and consider the “language” of “silence”, the ways in which memory and identity can survive and re-emerge from deliberate obliteration. “I study my own identity” she says in another poem, “Out of the fragments of / A colonised past”.

Another link I noticed was between Parvathi Solomons Arasanayagam’s mother Jean Arasanayagam and the final poet in the anthology, Richard De Zoysa. They both wrote poems entitled ‘The Poet’, and holding the final stanzas of these two poems up together brings out both the light and darkness, the hope and the hopelessness of this poetry of civil war and witness.

Arasanayagam:

She tells herself, ‘I am common Anonymous like all the others Here. No one knows that I have magic In my brain.’

De Zoysa:

i am the storm’s eye ceaselessly turning around me the burning the death the destruction the cliches that govern the world of the words of the prophets and preachers, and maybe the saviours are lost to my peering blind eye in the dark

What Arasanayagam calls magic, De Zoysa calls blindness – the eye which reflects “nothing / but truth”, the blindness of the “well favoured men of the hour”. And yet, De Zoysa also – earlier in the poem – refers to the poet’s “magic” and the way it allows readers/viewers to “fashion / their truths”. Perhaps the magic both poets are talking about is that part of what was in them which survives to be collected, read and passed on to readers of anthologies like this one.

Knowing that De Zoysa was abducted and murdered in 1990 due to his involvement with Marxist militant organisation the JVC, makes his “blind eye in the dark” as the final words in the anthology not only poignant but key to understanding the profound political anger of the project as a whole. A poetic voice which was silenced, “anonymous like all the others”, is here able to speak again and along with all the other poets represented, refuses to allow the memories of a half-century or more of injustice, to be forgotten.

I feel compelled to pick a favourite from the anthology to finish on, because there is one poem which I found moving beyond all others. ‘Grave Song’ by Cheran and translated from the Tamil by anthology editor Shash Trevett (whose pamphlet ‘From a Borrowed Land’, I reviewed here) seems to distil all the horror and despair of atrocity upon atrocity into a single image of a man digging his own grave, it manages to capture the complex relationship of a people to a place even when they are ripped apart over many years, and above all it finds a way of pulling a sense – metaphorical, but a sense nonetheless – of Life from Death, suggesting as it does so that there is a shared community in the losses experienced by the Sri Lankan people.

I hope I am not in infringement of copyright if I quote the poem in its entirety:

Alone with the three whose faces and hearts were hidden in darkness he dug his own grave. his distress, the horrors he felt were trapped within his unspoken words which congealed in the air above the grave. The wind would not permit the rain nor the sun to approach them. Those unspoken words sank into the soil entering the roots of trees. The unceasing wind drew them upwards in waves radiating them along branches from leaf to leaf and beyond. There are no ghosts above that grave. Nor gods. There is no memorial stone. Encased in the cruel grip of time, a single patti flower grows upon his grave, burning bright like a lamp on a darkened street. In his final words lives the life of our land.

The books on Sri Lanka which are recommended by the editors in their introduction:

The Cage – Gordon Weiss

The Seasons of Trouble – Rohini Mohan

Still Counting the Dead – Frances Harrison

Thank you for making me aware of this collection and the final poem you selected.

LikeLiked by 1 person