Part One

Danez Smith recently said something in the Guardian which caught my attention. They said: “I want my work to be useful”.

This is hardly controversial and is, I have always presumed, what many poets and artists in general feel about their work, but what struck me immediately was how rarely I have actually heard anyone express it. The only other example I could think of was Denise Riley speaking about how her work in Time Lived, Without its Flow seemed “needed”. As I ruminated on this, and as I thought about the poetry I have read over the years, I started to question my original presumption. A lot of poetry discusses complex issues, holds difficult emotions and situations in unusual lights to help us see them and begin to understand how to deal with them, it allows us new ‘ways of seeing’ to use the old phrase, so I suppose to that extent it is useful. But do poets write to be useful? Or do they write to help themselves through something, or simply to express something they feel the need to express? Or (less generously) to hit the right topics, the ones that will get them published and be popular with the poetry reading public? Or to display their skill, their craft? Or to consolidate their position in the ‘Canon’ (whatever that is) and be remembered by future generations? ‘All, some, or none of these’ is the obvious and not particularly helpful answer. And perhaps motivation is not the point anyway – poetry written for all the above reasons might still be useful to any given reader. But if I’m writing poetry, I also want to be able to say it is useful, and I want to write it to be useful, actively useful in real sense.

So this brings me back to Danez Smith, a black poet writing for black people in their new book Homie, but for a wider, whiter audience in their award-winning Don’t Call Us Dead. Smith’s work is clearly useful in giving voice to an uncompromising and clear-sighted black anger that white audiences need to hear, to rattle the bars of institutional racism. In the US, Smith’s voice is not alone: Claudia Rankine, Terrance Hayes, Jericho Brown, Ocean Vuong, Don Mee Choi are just the names which come immediately to mind. All of them writers of colour writing ugently and ‘usefully’. Their voices are useful not only because of their individual talent, power and beauty, but because of the minority perspective they bring to the majority, dominant – let’s face it, white – culture. They challenge traditional and patriarchal forms (what Audre Lorde called “the word games of the white fathers”), they oppose the white male gaze, they extend what the culture of a white-dominant country is capable of encapsulating and expressing, and for all these reasons and more their poetry might actively make a difference to society. There are voices in the UK about which we could say the same: Jay Bernard, Vahni Capildeo, Sarah Howe, Kei Miller, Mary Jean Chan, again these are just the first names that pop into my head.

These are dynamic, vital voices. ‘Useful’ ones. But could a white poet write usefully about race? I don’t know of any who have tried, or at least who have tried and been published. It would clearly be a risky endeavour (see Part Two below) not least because if too many white poets did try and did get published on race, they would ultimately be likely to drown out the voices of colour and end up working to uphold the very structures that the work of their BAME peers challenges. But there are compelling reasons why a white poetry of race (a genuinely self-reflecting one) could have a ‘useful’ role to play. To provide a background on why I think this is the case, I would recommend two American texts in the first instance, White Fragility by sociologist Robin DiAngelo, and this thoughtful piece from The American Poetry Review by poet Joy Katz ‘Awake In The Scratchy Dark: On Writing Whiteness’. These texts are focused on American experience, but I haven’t found any specific to the UK (which is interesting in itself) and although there are differences, I think the similarities are sufficient to make them relevant here aswell. Part Two of this blog is about how difficult, as well as potentially risky, it is for a white person to write about race and – because I’m writing from the UK – about empire (from which British structural racism is inseparable).

Part Two

I’ve spent the last year and more attempting to write poems about race and the legacy of empire in the UK. Some of these have been okay, some pretty good, some terrible; all of them remain unpublished at the time of writing, and I’ve never posted any of them on my blog. Without looking for an “Aww, you poor lamb”, I must say, it’s not easy for a white person to write honestly about race and empire in the UK. I’m sure it’s not easy for anyone, but I’m white and so that is what I’m qualified to talk about. Why isn’t it easy? Well, on one level of course it’s obvious to say that published white poets, or white poets who want to get published, are nervous about saying the wrong thing and ending up actually getting something published which then prompts a career-ending twitterstorm and blaze of publicity. This is true – and I imagine editors have similar nerves around any white-written, race-based submissions they may have received (not all publicity is good publicity, if that myth was not debunked before social media came along, it surely is now) but it’s a bit poor, isn’t it? I mean, the nerves are understandable, there really is a lot of senstivity and anger around this issue, but let’s not be cowardly: white attitudes to race and empire matter, if only because those voices which represent and constitute the hegemon need to change if anything is going to change. There’s another obvious reason, too, this: white liberal/left poets (I’m not sure I need the slashed adjectives here – pretty much all UK poets fall somewhere on that spectrum, don’t they?) are likely to feel that white voices should not be cluttering up the spaces where voices of colour need to be heard more. They (I should say we) are quite right about this, but again I don’t think it will quite do. As Reni Eddo-Lodge pointed out in ‘Why I’m No Longer Talking to White People about Race’, white people will never be ready to talk to people of colour about race and ongoing structural racism – and therefore begin addressing social change – until they are able to talk to each other about it openly and honestly. It seems to me that poetry, with its capacity for concise and acute self-reflection is the ideal place to start doing this. A third reason might be that white poets genuinely don’t think we have anything to add on this issue, that we should step back and allow poets of colour to say what needs to be said because racism happens to them, not us. For a third time: this is not good enough. As DiAngelo says, thinking that racism is only an issue for people of colour is a classic internalised strategy for deflecting responsibilty. Beneficiaries of power rarely notice that they are beneficiaries at all, and those who have always stood at the podium cannot always see that they have been artificially elevated above the crowd. Until the present generation of black and Asian and mixed-race voices came of age and began speaking with clarity and strength, voices of colour, although they were there (and strong, clearly, you only need to think of Benjamin Zephaniah), they were relatively easy for the ‘85%’ to ignore, simply because they were not present in any numbers. This, I think, is no longer the case. Demographics are changing. We, white people, have to think through who we are and how we got here – and to talk it through.

But there is another difficulty for the white poet, a more profound one, and that is the fact that genuine self-reflection, which engages with a diversity of voices on national history, and which takes in all the many and deep ramifications of skin colour, family history, cultural memory and social structures, and which listens to and believes experiences which might seem peripheral to one’s own, and which sees the connections between all these things and is able to relate them back to the self, all this is likely to be painful. It will be easier for the white poet, no doubt, to feel (or perhaps to appropriate) the anger felt by many people of colour, and to aim that anger outwards, self-righteously positioning ourselves as ‘in-solidarity-with’. That is one response. No one wants to align themselves with the oppressor. But more difficult is looking inwards and being prepared to find and accept various levels of privilege, ingrained racism, denial and, yes, fragility. That a white poet will find these is almost beyond doubt, and when we do (this is the really tricky part) we will need to decide what to do about it.

Activism is not the purpose of this blog, poetry is, but I feel increasingly convinced that there is an area – not in the anthem (“Rise, like lions after slumber/In unvanquishable number”), and not necessarily in the poetry of protest (“The furious young/ran towards her through the fields of wheat”) – but somewhere less defined where these two, activism and poetry, cross. I believe the arts can act most effectively at a level below that of protest and anthem, at a level of collective cultural awareness and ultimately memory, where it can operate to either strengthen existing social structures or question and challenge them. I am far from an expert on Cultural Theory and so I would be surprised if this is anything revolutionary, but it is where I come back to what I said in Part One about being actively useful – I am advocating poetry as activism at the level of cultural memory.

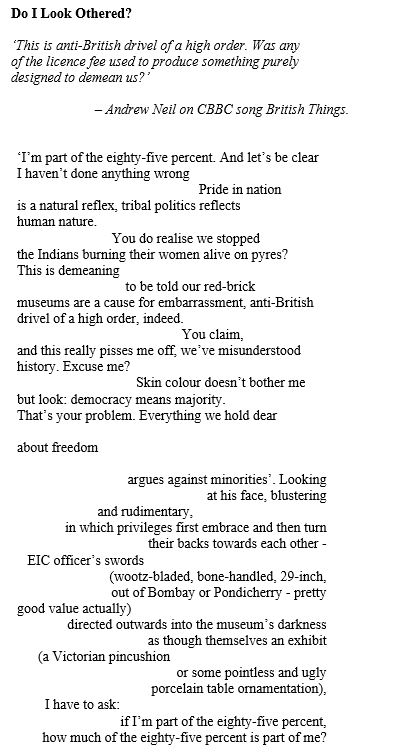

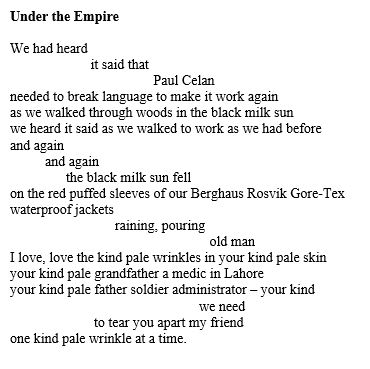

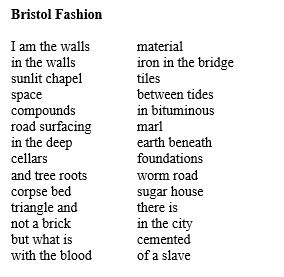

I wouldn’t normally post my own poems as part of an essay on my blog, but in Part Three I will, in order to illustrate ways in which poetry might at least try to self-reflect on the legacy of race and empire. I’m not arguing for the quality of the poems, just for their attempt, in the ways described above, to be useful:

Part Three

Three Poems

*

Some reading/listening that has informed this post:

Why I’m No Longer Talking to White People about Race – Reni Eddo-Lodge

White Fragility – Robin DiAngelo

Natives: Race and Class in the Ruins of Empire – Akala

Capitalism and Slavery – Eric Williams

The Anarchy – William Dalrymple

We Need to Talk About the British Empire – Afua Hirsch (6-part Audible series)

Your Silence Will Not Protect You – Audre Lorde

Awake In The Scratchy Dark: On Writing Whiteness – Joy Katz (article, in The American Poetry Review)

Thank you for being thoughtful and heartfelt with this post.

Two or so, perhaps related–who knows–thoughts on what you’ve said.

The real task and aim of art is understanding, even for those that are motived in complex and less noble ways. That we can never know, that all communication can be misunderstood, that there is always another know beside the one we think we have momentarily grasped, doesn’t stop this.

Intersectionality has a connotation of buzzword, but the music underneath it must save us. Racism divides us, sticks us in lanes, and yes it’s powerful in it’s effect. No thinking, no knowing, no attitude of denial has yet stopped making it powerful. “Yet” is still a word of hope. Cultural heritages are something we hold onto as warm, family arms–even if the family isn’t perfect. When bombs fall, when natural disasters strike, people try to get home. But intersectionality, that funny “woke’ word, means that we have no single home, no single class of thing we think we are. Class distinctions and experiences have been held up as one such thing. Do two working class people share some home truths, even if they are otherwise different has long been a response. Gender, sexual orientation too. Regional and national locations. Religious beliefs. Even hobbies, sports, and passtimes.

May I go further: being a poet is intersectional. Two poets with different DNA mixes, different cultural heritages, even different poetic styles are still both poets, they share that. As do musicians, or other artists. The point of the underlying music under the awkward word intersectionality, is not to find smaller containers, but to say that we leak into each other. That’s why art works, even though it always fails to some degree. Given that, that we leak into each other, you recognize that one can’t use ignorance, prejudices, and lack of understanding as excuses to avoid this.

The questions you’re asking yourself and other readers of your piece about doing work from a position that contains privilege elements, I don’t have anything useful to say or echo back. I feel more in the dark on that matter at the moment.

LikeLike

Thanks very much for taking the time to comment, Frank.

LikeLike

Important stuff, Chris. As you know, I deeply share your concerns: “But more difficult is looking inwards and being prepared to find and accept various levels of privilege, ingrained racism, denial and, yes, fragility.” Totally. And, of course, guilt. And yes, working out what to do about it, poetry-wise, is far from easy. I’m very much looking forward to your next posts on the subject.

LikeLike

Thanks Matthew, yes I hope this is a conversation which will keep moving forward. Guilt is an interesting and complex part of it I think – an emotion which can become a tool for progress or a catalyst for anger of one sort or another. As I think we mentioned in our previous conversation on this, I think we can learn from the German experience of working through the legacy of the Holocaust.

LikeLike