Everyone loves John Keats.

I’ve looked for #KeatsHate online just to see if it exists – there is hate for everything else after all – but as far as I can discover there is nothing in the modern world but love for this particular JK, love for the poetry and love for the man*. If the haters are there, they’re keeping very quiet. My conclusion is this: those who love poetry love Keats, and those who don’t love poetry don’t care enough about Keats to hate him. Perhaps now, 200 years since his death, is the wrong moment to be looking for criticism of the man and his work, but thinking back I don’t believe I’ve ever heard anyone express serious reservations – not unless you go right back to the classist snobbery of Yeats. And I’m not about to set a precedent, but I am interested in why his stock remains so high, particularly amongst poets themselves.

It is a paradox, but true I think, that one of the reasons he remains so well remembered and so well loved is exactly because he is so well remembered and so well loved. Even for those whose tastes do not run to the Romantic, Keats represents the kind of poetic longevity every poet hankers after, whether they admit it or not. All literary writing is a bid for immortality, even the ancient Egyptians sensed something along these lines. Keats was intensely aware of this, and the cynic in me is tempted to read his final request of Joseph Severn to have ‘Here lies one whose name was writ in water’ inscribed on his gravestone as one last, slightly duplicitous but nonetheless genius attempt to make such a bid. Like Shakespeare, Keats is living the kind of literary afterlife we all aspire to but which none of us will achieve (and yes, that includes you, 99.99% of published poets). Poets love Keats, in part at least, because they want to be him. They want to be one of the tiny fraction of poets who poets and readers will still be admiring and taking inspiration from in 200 years’ time, and that Keats did it means they can do it too.

It might also be worth noting that the suffering artist who was not properly recognised until after their premature death is a seductive cliché, and one which strikes a deep and resonant chord with poets’ Inner Bohemian. Often the origin of this cliché is located with the Romantics themselves, but I find it tempting to look back 2,000 rather than just 200 years to that other great and noble sufferer, Jesus Christ, whose torment on the cross still inspires more than any other, whose struggles and early death point towards greater, more permanent truths. The poetic ego internalises Christ’s pain and appropriates his immortality, and by extension that of the Christ-like Keats. ‘If I am nothing today’, the poet tells themself, ‘what does it matter when I am to be a God in 200 years?’

Too much? Maybe.

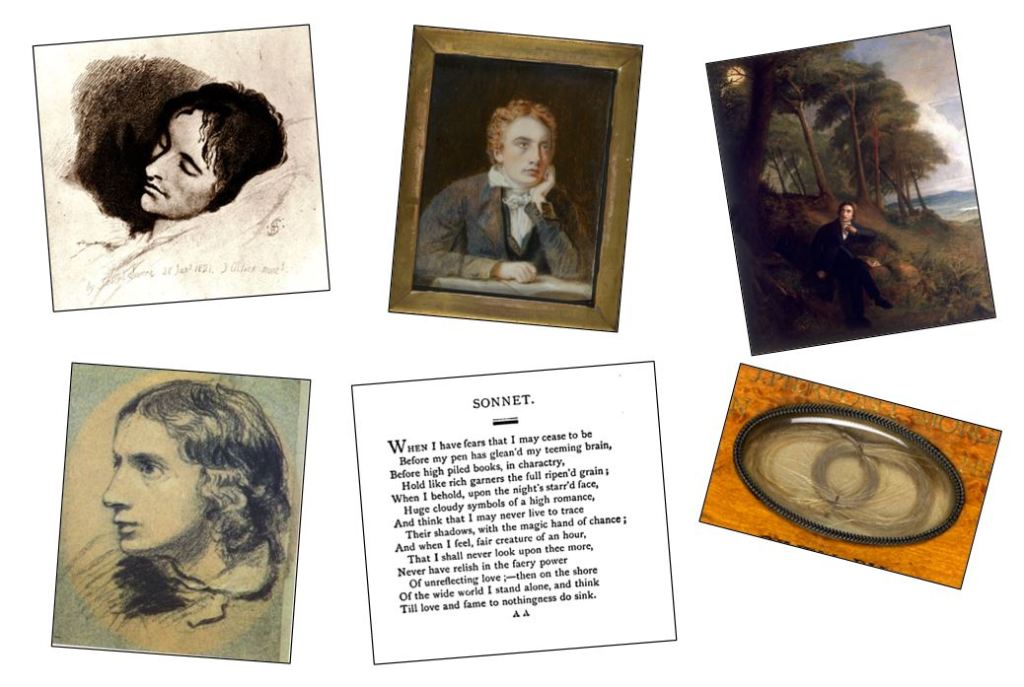

At any rate, unlike Christ, or Shakespeare, the details of Keats’ life are more than hearsay, guesswork and legend. His medical training, his literary friendships, his contemporary reviews, his tragic “family disease”, and more than anything his intense love for Fanny Brawne are well documented by both Keats himself and by those who knew him. FR Leavis thought that Keats the man disappeared entirely from his verse, and this may once have been so, but in this Age of Celebrity I don’t think it is any longer. The facts of his life are like accessories that hang from his poems, decorating and complimenting them. This is where Keats differs from other poets of two centuries ago who are also still remembered, read and valued. There are no others whose lives so perfectly enhance the tone of their poetry – Wordsworth’s move from revolutionary to reactionary, for example, has the opposite effect, as does Byron’s lordly philandering and arrogance.

To modern sensibilities, Keats’ life has the benefit of not being overly-privileged (unlike most of his contemporary poets he was from the lower end of the middle class), of being short (he did not have a chance to grow old and give us cause to dislike him, á la Wordsworth), and of being a gratifying confluence of misfortunes which give his 25 years an attractively readable narrative (the death of his father, then his mother, then his brother; the debts; the hurtful reviews; and finally his own death from tuberculosis). And then there are those letters. Oh… (or perhaps I should say ‘O…’) those letters! The intelligence, the searching curiosity, the pain, the vulnerability, the embarrassment (thank you Christopher Ricks) and the sheer humanity that comes through them like a great highlighter pen emphasising those qualities in his poetry. They are there in the poetry anyway, but how much more do we notice them as a result of knowing his letters? And how many, I wonder, have fallen for the letters first, only subsequently becoming enraptured by his verse?

His poetry too, it goes without saying, is rather good. And I don’t mean to disparage it by saying that like Roald Dahl and Julia Donaldson, Keats is extremely ‘readable out-loud’; in terms of a writer’s ability to remain in the public consciousness this is no small thing – Eliot and Homer have the same quality. The luxuriance of its sensuality that plays in the mouth so satisfyingly is its key strength in this respect (and the means by which Keats elevated the Romantic project, then in its second generation, to new heights, pushing it towards the Victorian era that would both consolidate and clog it up). And so we can add to his misfortunes the extraordinary and intense quality of his work – distilled, again satisfyingly, in that one almost impossibly creative year of 1819 – and again it is hard to avoid the religious connotations of an individual being touched by a genius which, if not quite divine, certainly feels almost visited upon his tormented young soul from some mysterious Elsewhere.

But what does Keats have to offer today’s poets in particular? Well, his particular strand of Romantic introspection may speak to the identities-centred worldviews that shape so much public discourse at the moment. The external becomes the internal, and the internal becomes the eternal. Truth, for Keats, is not to be discovered by the scientist ‘unweaving the rainbow’ with their ‘cold philosophy’ but by the poet imagining a silent voice in the designs engraved on a Grecian urn. What is true, then, is mediated through the individual consciousness rather than dictated by the tenets of logic and empiricism. This seems to chime at least with many contemporary perspectives on literature, history, gender and race. If Keats continues to resonate with a new generation of younger poets, could this be part of the reason?

Linked to this might also be the fact that the Romanticism Keats represents is emphatically ‘not Modernism’, which developed as a reaction against it, and whose Big Name Poet practitioners (Pound, Eliot, Stevens) are seen by many as supporters of a conservative and in some cases fascist politics which is anathema to liberal contemporary poets.

This brings me to me to one final possible reason for Keats’ longevity: that his poetry is a looking rather than a finding, a question rather than an answer, it is the journey to a place rather than the arrival at that place. His idea of Negative Capability (that someone might be “capable of being in uncertainties, mysteries, doubts, without any irritable reaching after fact and reason”) reminds us of a fundamental quality of the human condition, which is easy to forget when almost everything we do is geared around making ourselves feel like we understand what we are and what surrounds us, that is: we don’t understand.

It is deeply consoling, I think, particularly at this point in time, as social media boxes us in, monetises our hopes and fears, and streams us along tracks of entrenched opinion, that John Keats is still there, still making his “awkward bow”, and still looking for truth, of all things, in, of all things, beauty.

*Actually, this is not entirely true, I found one negative assessment of Keats, here, but as sophisticated as it is, I’d be surprised if it’s written by a poet so I’ve decided not to let it interrupt my take.

One thought on “‘I would have made myself remember’d’: Why Poets ♥ Keats”