A few months ago, I saw Sasha Dugdale talking to Maitreyabandhu at the London Buddhist Centre for the launch of her latest collection The Strong Box (which I reviewed here). It was a fascinating conversation (which you can watch here) for many reasons, but I was particularly interested to hear their comments on the fact that Dugdale, in a collection extremely rich in allusion, chose not to provide an explanatory Notes section. Maitreyabandhu was, I think, surprised that there were no notes and said he did not get the impression Dugdale was using allusion “for intellectual reasons”. I agree, and I had recently read the collection for my review and found it very refreshing that notes were not included. It is not that notes are not helpful – they really are, but I have often felt like there is both something limiting about them (‘this is what I’m getting at’ the poet sometimes seems to be saying) and in some cases something just a little ‘showy-offy’ going on. I don’t object to them being there, I get pleasure out of reading them and find it useful to apply them to my reading of the poems, and yet there is something about them that makes me feel like they shouldn’t be there; it is a sensation that I will return to later in this essay, one which could be described (rather grandly taking the term from the lexicon of psychology) as cognitive dissonance.

In fact, Dugdale later explained a little further to me in an email that her intention in The Strong Box was to “make a new and integrated language from disintegrating canons”, implying I think that notes pointing directly to the allusions would have made such a language less natural and detracted from the overall effect she was seeking. This approach seems to me one which is fundamentally respectful of the readers’ role in generating a text’s meaning – as I put it in my review “The Strongbox is like the TARDIS, it is an immensely rich poetic world which, when you enter, you find is bigger on the inside than it is on the outside. You, reader, must discover; you must curate.” The poet puts her trust in her readers to read the language she is creating from those “disintegrating canons” and she allows them to curate her collection with whatever interpretive tools and poetic knowledge they happen to bring.

All this made me think about a book I read recently called Intimacy and Integrity by Thomas P. Kasulis, a comparative philosopher from Ohio State University. I feel this work has a lot to offer both the study of poetry and the study of culture more widely, and so I had been looking for a chance to discuss it here in my blog.

I will briefly outline Kasulis’s thinking here, with a few additions of my own, before returning to The Strong Box and its lack of notes.

Kasulis suggests that when making cross-cultural comparisons, one useful model to help us make sense of difference may be to think in terms of “recursive cultural patterns” which he calls “orientations of ‘intimacy’ and ‘integrity’”.

Intimacy and Integrity orientations describe two different hypothetical ‘starting points’ or inclinations in thinking which place differing weight on certain aspects of the relationship between the Self and its environment, of relationships between Selves and other Selves, and of the nature of Truth itself.

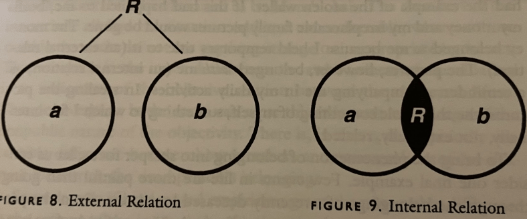

Some cultures (traditionally those termed Western) emphasise integrity in the sense that individuals are seen as complete and separate entities in themselves – i.e. with their own indivisible wholeness or ‘integrity’; and the relationships between those individuals are something external to them. Other cultures (again traditionally, Eastern) in contrast emphasise intimacy in the sense that individuals are fundamentally part of each other, inseparably sharing of one another’s innermost qualities. The relationships between individuals viewed this way are internal, part of both and separate from neither.

These fundamentally differing orientations have enormous consequences for worldviews, ethics, aesthetics, and politics.

For example, a scientific view of Knowledge as publicly verifiable propositions about an externally existing universe is a worldview which is an outcome of an integrity orientation-based culture. Knowledge in this worldview, is in principle available to all (in journals, conferences etc.). An individual is a discrete thing: the knower; a certain state of affairs in reality is a discrete thing: the known; and Knowledge is descriptive of the relationship between the two, while being external to both. But the intimacy view of Knowledge sees it as part of both the knower and the known. The judges of a dance competition know how to score each dancer not because of a publicly verifiable set of propositions about dance, but because they have the expertise and crucially the experience of dancing that allows them access to this knowledge. It is not subjectivity; it is objectivity accessible only to some. With intimacy, the knower and the known are part of each other, and the truth of Knowledge comes from a process of what Kasulis calls ‘assimilation’, in contrast to ‘correspondence’ theories of truth in integrity orientations (the correspondence between a proposition and a state of affairs).

Similarly, an integrity orientation would see God and a believer as separate, while an intimacy orientation would see them as part of each other; a worker with an integrity orientation would be more likely to see employees as separate to the company they work for, whereas one with an intimacy orientation would see the two as part of the same thing – each fundamentally affected, changed and formed by the other.

Politically, the left-right duality of ‘Western’ discourse is a feature of the atomism and bipolarity that comes from an integrity-oriented epistemology, as is the party system and representative democracy (clearly, though, not the necessary result of this orientation); while the more esoteric, exclusive, and ‘hidden’ nature of knowledge from an intimacy-oriented standpoint, can under certain circumstances lead to fertile conditions for despotism, fascism and totalitarianism (although again history shows us that these political ideologies do not depend on intimacy-dominant cultures).

Kasulis’s aim is to make sense of some cultural clashes and misunderstandings and to foster greater understanding of greatly differing philosophies. My view is that it does this extremely successfully and it is important that he notes integrity and intimacy as features of not only cultures but of sub-cultures. Whereas one orientation might be dominant in a culture overall, another may be dominant in a subculture within that culture. And moreover, that orientation may change from legitimacy to intimacy and vice versa over time. With globalisation and particularly since the birth of the internet and social media, it seems likely that these orientations may have become more and more fragmented, sub-cultures more profuse and spread out – and so what is designed as a framework for understanding differences between, say, Japanese and American culture, may be equally useful in helping us understand the many and bitter disagreements and disputes that make up what are known under the blanket term Culture Wars.

It is important to note that there is no suggestion that an intimacy or an integrity orientation is better or more appropriate than the other, only that looking at cultural difference in that way may help us navigate clashes and avoid falling into division and distrust. If we understand global cultures as having gone through a process of fragmentation over the course of the twentieth century, and that fragmentation having sped up significantly over the last thirty years of increased internet usage, we can perhaps apply Kasulis’s model to help us make sense of seemingly intractable and inexplicable differences: if our thinking is now affected by both intimacy and integrity orientations, because our influences come in from all over the world and algorithms may cause the cohering of sub (and sub-sub-) cultures in every smaller and myriad online clusters, maybe what Kasulis sees as larger scale recursive patterns have actually become more localised and faster evolving than he imagined. Could it be that when I get blocked on Facebook by an angry family member because I’ve expressed positive views about Trans women, that I am applying intimacy-oriented thinking to the issue of gender while my family member is more influenced by integrity-oriented thinking? When I am unfollowed on Twitter/X by an angry poetry editor who has interpreted my submission as racist, could it be that I am applying more integrity-oriented thinking to the issue of race while the poetry editor is applying intimacy-oriented thinking? In other words, with disparate influences coming in thick and fast, have the orientations effectively exploded? None of this makes one person right and another wrong on any given topic, but thinking about Culture War flashpoints through the lens that Kasulis supplies may enable us to frame the differences between us in helpful ways.

Let’s turn to ways in which Kasulis’s ideas can be directly applied to the analysis of poetry; which he deals with in a section on aesthetics. Under integrity, the artist “retains autonomy and individuality through her or his creative expression”, the artwork itself remaining separate from both the artist and the audience, the relationship with the former being their expressive intent and with the latter their interpretation. This, I think, is the orientation of the poetry critic who makes unambiguous quality judgements about a poem and backs up their judgements with quotations. I would suggest that it is also the orientation of the poet who includes explanatory notes at the back of their highly allusive collection.

Creativity under an intimacy orientation, however, is an internal relationship to both the artist and the world; and a work of art contains (and is contained by) not only the artist and the world, but also the audience. An intimacy view of aesthetics has several interesting implications: one is that determining the meaning of an artwork is left neither to the artist nor the audience, but because it is part of both of them, and they of it, its meaning is down to both. But, as with intimacy’s epistemology, there is a requirement of experience and expertise in order to ‘uncover’ the work’s meaning (“those who have assimilated knowledge through common praxis”). It is not necessarily open to all, only those who put in the time and effort to ‘get’ it. This is the orientation of the poetry editor making their selections for inclusion in their magazine, and that of the panel of poets choosing which poems are shortlisted in a competition. I feel it is also the natural orientation of both modernist and post-modernist poets, whose texts may variously make use of esoteric allusion and refuse stable meaning.

So, returning to Sasha Dugdale’s non-use of notes in The Strong Box, which we might compare to another excellent recent collection, one which does make use of notes, Geraldine Clarkson’s Medlars (which I reviewed here), I think that one way to consider her project is to say that Dugdale applies an intimacy-oriented approach. The poets of those “disintegrating cannons” and their work, are part of her, and so they are intimately part of her work. To pull them out in notes would be to externalise them, which does not fit with the internal relationship she feels to them. Her readers may notice them, or they may not, depending on what of those canons is also in them. In contrast, Clarkson’s notes indicate that she may be taking a more integrity-oriented approach: she wants to externalise those people and works that have informed her poems. Her notes are there as a useful tool for the clarity of readers; Clarkson does not wish to confuse, and she wishes to be open about certain aspects of where the poems came from, and so in her case adding notes is a thoughtful act. But they are an appendage to poems which are seen as separate to both the poet and the reader.

Again, there is no suggestion, either in Kasulis or here, that either orientation is right or wrong. This is a way of thinking about difference, nothing more. It is not principally about poetry of course, but for me poetry is a useful way in to thinking about something more widely.

My feeling of cognitive dissonance on coming across explanatory notes could be explained by me as a reader taking a more intimacy- than integrity-oriented approach (and this in fact ties in with the way I was trying to make sense of poetry and ideology in my essay on Spender and ideology here) even though a lot of what I do as a reviewer (arguing a case, presenting evidence) might equally show integrity-oriented inclinations. To expand this, could it be, when we come across some cultural phenomena that just doesn’t ‘feel right’ but we can’t quite explain why, or when we have mixed feelings about something that we don’t quite feel able to pin down, that intimacy and integrity may offer an insight as to why? And might the same be true if the dissonance is not in me alone, but between me and others? If I am right that the “recursive cultural patterns” in Kasulis have ‘exploded’ and ‘fragmented’ with recent changes in global communication norms, then his model may provide insights into why so many people everywhere are disagreeing about so much.

This is a brief and inadequate precis of Kasulis’s work on intimacy and integrity, and for anyone who is interested in learning more, I would highly recommend the book itself, which you can find here.

You can buy The Strong Box here.

You can buy Medlars here.

The book sounds very interesting, Chris. I’ve hitherto been firmly in Geraldine’s camp: I use notes chiefly to explain cultural references which not every reader would know, because I think it’s generous to the reader and stops them having to look them up online. But it’s good to reconsider their value – and especially if they add a fact not alluded to in the poem.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for commenting Matthew. Yes, I absolutely see the value of notes, and Geraldine’ are useful for exactly the reasons you mention. And of course a point I didn’t make in the essay is that the reader is perfectly at liberty to ignore them! But I am fascinated by the implications of not including them in highly allusive collections, for both writer and reader.

LikeLike